“Heaven looks different when you have all your family up there. It’s hard to turn the page, knowing that in the next chapter of your life they will no longer be there.”

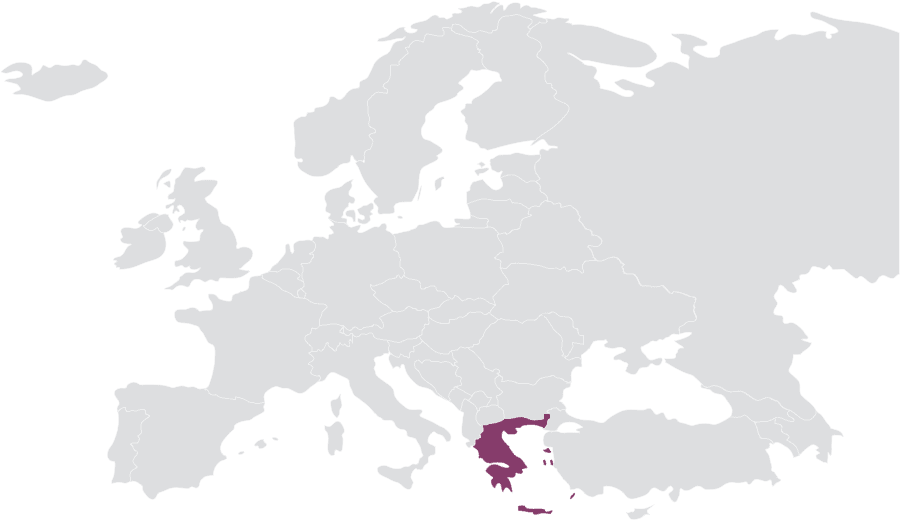

This is an excerpt from the memoirs of an 18-year-old staying in a special centre for underage refugees who made it to the Greek island of Lesbos on their own. Hanging on the walls are their written attempts to come to terms with their new situation. “It is so irrational, and in the most painful sense of the word, that the person who gave me life cannot celebrate my birthday with me,” the teenager further writes.

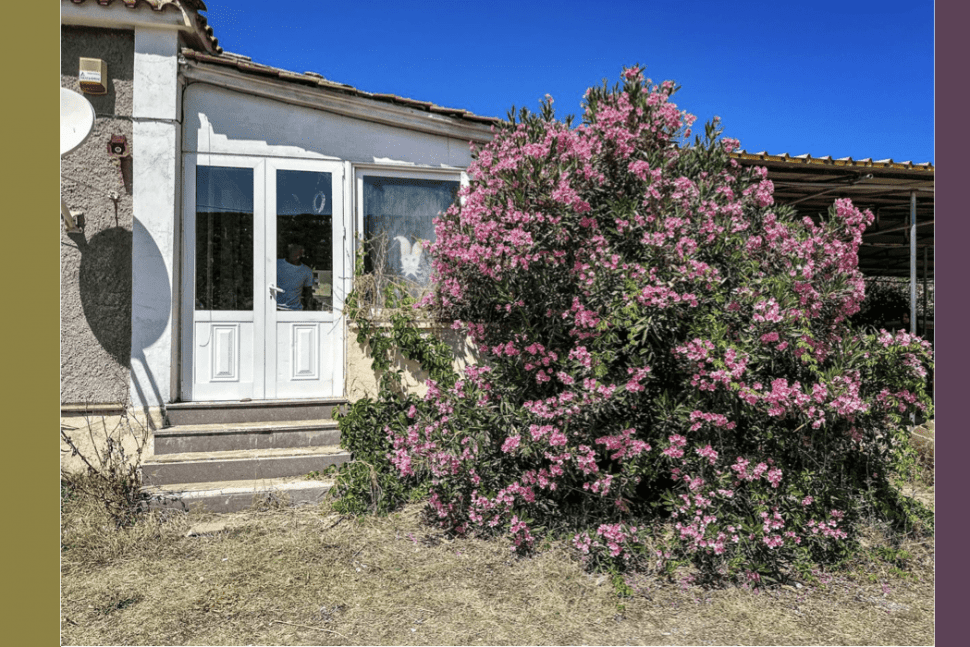

The centre, located 20 kilometres north of the island’s capital, Mytilini, now houses 18 minors. They are from Eritrea, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Nature is slowly consuming the place and the buildings are decaying from old age. The setting, something that used to be a taverna, and the bungalows around it, stirs up images of a time when Greek sun-seeking tourists spent their holidays here. Today it is quiet. The new guests don’t make any noise; they are no longer rambunctious children. They are no longer amused by the sea, the sand and the sun. When they fled their homelands, there was no room to pack up their childhood. They had to grow up in an instant.

Ibrahim is 16 years old. He arrived here from the DR Congo. We sit down in the dining room. I tell him about our hospital in North Kivu. I say it’s hard, the war, but the country is beautiful and the people are open. He knows. He fled the war. The boy’s face no longer has the glow of a teenager. He has seen more than he should have. He has grown older, matured, weighing every word. A spontaneous joy and surprise that someone has spoken to him in French for the first time here tries to break through his expression. He is tough. Little things like this no longer make him happy.

It all started with a single photograph. A tomato, a slice of cheese and a tattered slice of bread. The daily ration. They were hungry and angry. The carers were heartbroken, but the food ration, which is brought in by catering, is out of anyone’s control here. They sent a photo and called Katerina and Nikos. They had heard that they cook deliciously for the refugees. They didn’t know if they would agree, but they had nothing to lose. The Greeks did the cooking and brought it to them. They have been here every day since. There was nothing to ponder at all.

“Apparently there are a lot of new kids in quarantine in the main camp without guardians. Any day now there could be a lot of us here again,” warns the centre’s caretaker.

“Let us know. You will not be short of food.”

We leave in silence. On the way, I look at the pictures on the walls. Everywhere, painted with crayons and markers, are the flags of countries. I realise that this is not an expression of patriotism. It is a memory of loved ones. Colours that will always be associated with mum and dad.

If you would like to do something good today, donate PLN 15 to them. It’s the cost of a meal, but also something much more. It’s an expression of concern that someone is thinking of them and reaching this time-worn place to care for them.