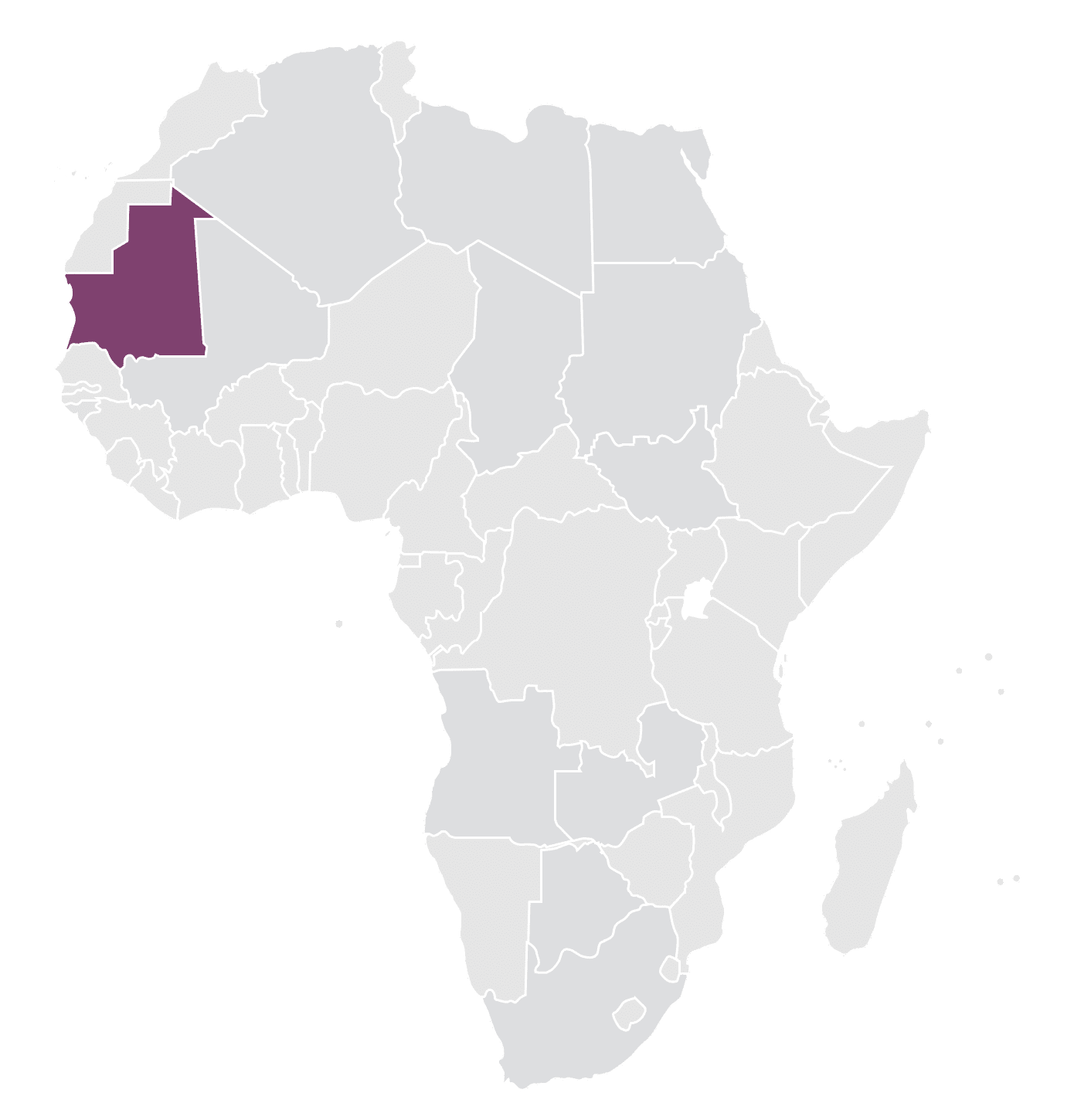

It’s a bit like driving a rover on another planet. I’m not sure which one. Hot, sandy, harsh, and unjust. 90% of Mauritania is just desert sand. Dust has been hanging in the air for a good week. We cannot see the sky. Everything is in sepia — a single fixed shade that enters the eyes, bites the skin, irritates the nose.

If the world ends somewhere, we are very close to that place.

“The Islamic Republic of Mauritania has religion written into its constitution. There are no Christians among Mauritanians. Everyone practices Islam,” explains Father Martin Happe, the bishop of Nouakchott. Next to him sits Father Victor, the bishop-elect, who will receive episcopal ordination in April and replace the retiring Bishop Happe.

The Catholic mission in this country is merely and entirely about being present, about engaging in social projects. Any form of evangelization would violate the rights written in the constitution.

We eat dinner together. In a modest house, not resembling a bishop’s residence. Father Happe sets the table, he scolds us when we get up to help. “You can do that when I come to your place.” We talk about how kindness begets kindness, respect begets respect. That one needs to listen to be heard and that these are the most important principles that allow a handful of Christians from other countries to be here.

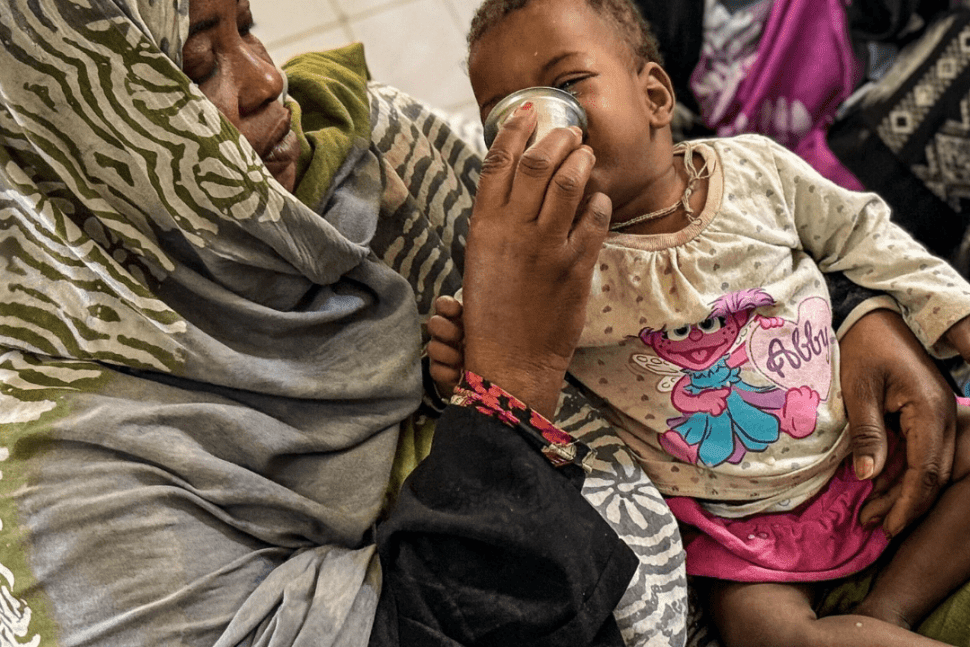

Bishop Happe, Sister Ewa, and missionaries from Atar and Kaédi teach us about Mauritania. We won’t change the customs and the culture because, in Mauritania, they are more than sacred. We won’t solve the problems, we won’t remedy the injustice. We are only allowed to be here, to listen, and to heal wounds. For us, that is “only”. For the people of Mauritania, thus “only” means saving the life of another child who, without our presence here, would die of hunger.