“I was the godmother of a child whose parents became tormentors. Thirty years ago, everyone here lost their humanity,” M. recounts the harrowing scenes. The memories grip her throat, choking and silencing her. Those who weren’t here can hardly imagine the witness accounts as real images—the stench of decomposing bodies, rivers stained with blood, madness in the eyes of the tormentors. Rwandans remember these vividly. They bandage these memories, yet the wounds still bleed.

“You know what I told her? ‘Go back to where you came from. Your parents have blood on their hands.’ I, the godmother,” M. recalls. A tall, upright, strong woman shrinks within herself. “I suffered because of that. I went to church and realized I was no different. You can’t just say that ‘it’s all your fault’. The price of justice cannot be revenge, for that is a vicious cycle and the violence will never end. I returned to my goddaughter’s home. I asked for forgiveness for how I had treated her. I’m friends with that family to this day, though thirty years ago everything divided us.”

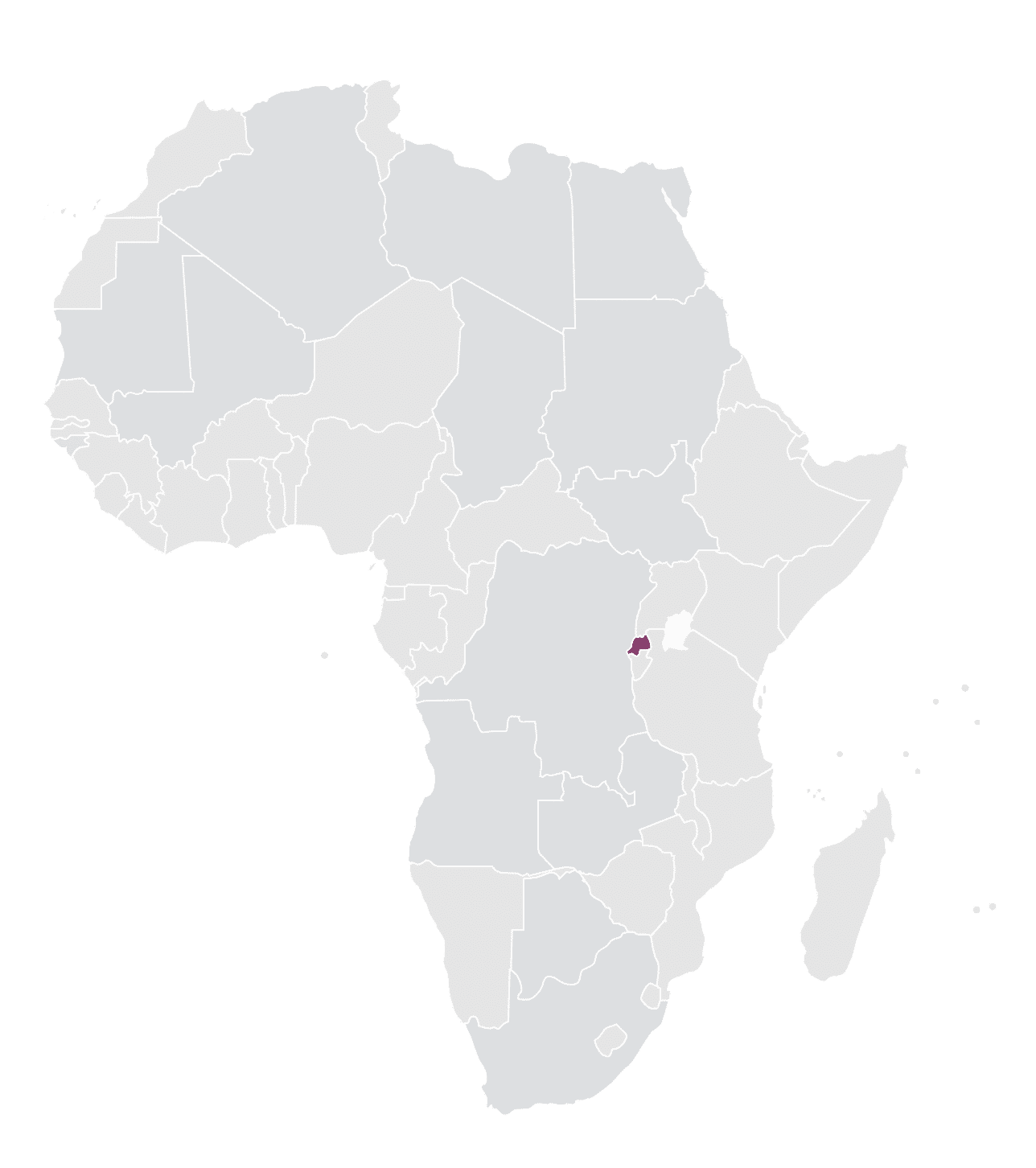

I’ve been coming to Rwanda regularly for ten years. I still have more questions than answers. I arrived during the week of “Kwibuka,” which means “We Remember” in Kinyarwanda. Exactly thirty years ago, hell opened up here, in the heart of Africa.

The country bursts with greenery all year round. Everything blooms wildly. It buds, sprouts, and rises. Nature manifests life, yet we talk about death.

“They slashed with machetes, hacked people, and poured salt into the wounds… My father died that way in May. You won’t understand it. It doesn’t help. No one wants to understand. Those who survived need a cup of tea, peace. Assurance that it will never happen again, that life does not have to end in pain and tears. One can remember either in order to never forgive, or to transform that memory into an effort to prevent anything similar from ever happening again.”