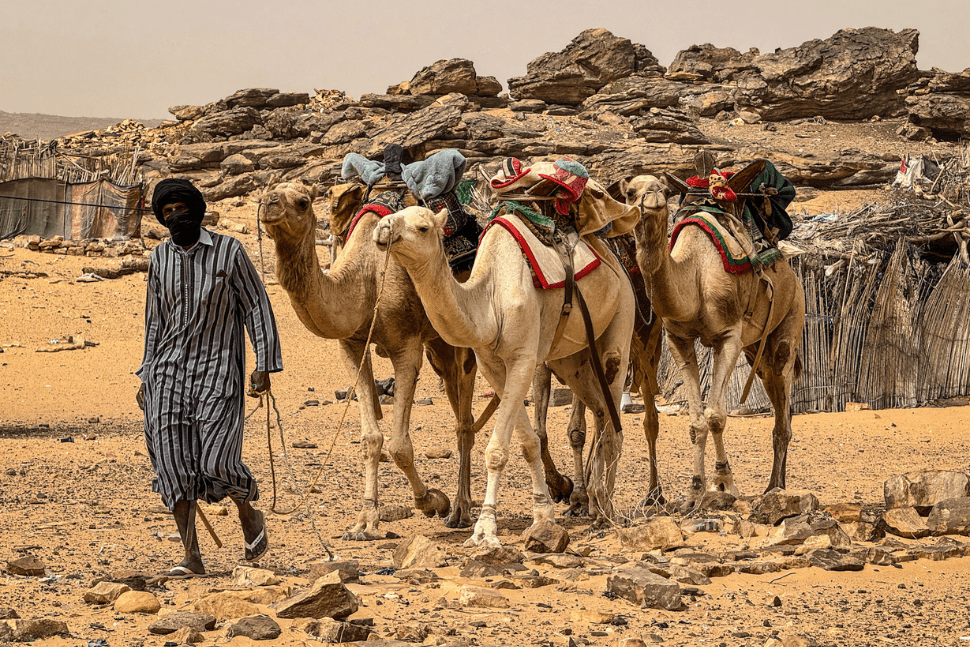

The Sahara is both beautiful and harsh. It commands respect. Tourists, who visit briefly, see its beauty but don’t grasp how harsh it is. For those who know no other climate, life here is easier. They understand that one does not argue with the desert. Any form of disobedience carries severe consequences.

Slavery doesn’t need bars or chains. Those are for people who know freedom. Those who have lived here for generations are enslaved mentally, they inherit servitude and fear freedom.

The caste system is powerful. It ensures everyone in the society has their place and fulfills their role. One knows not to step out of the bounds of their assigned position, not to aspire beyond what their status allows.

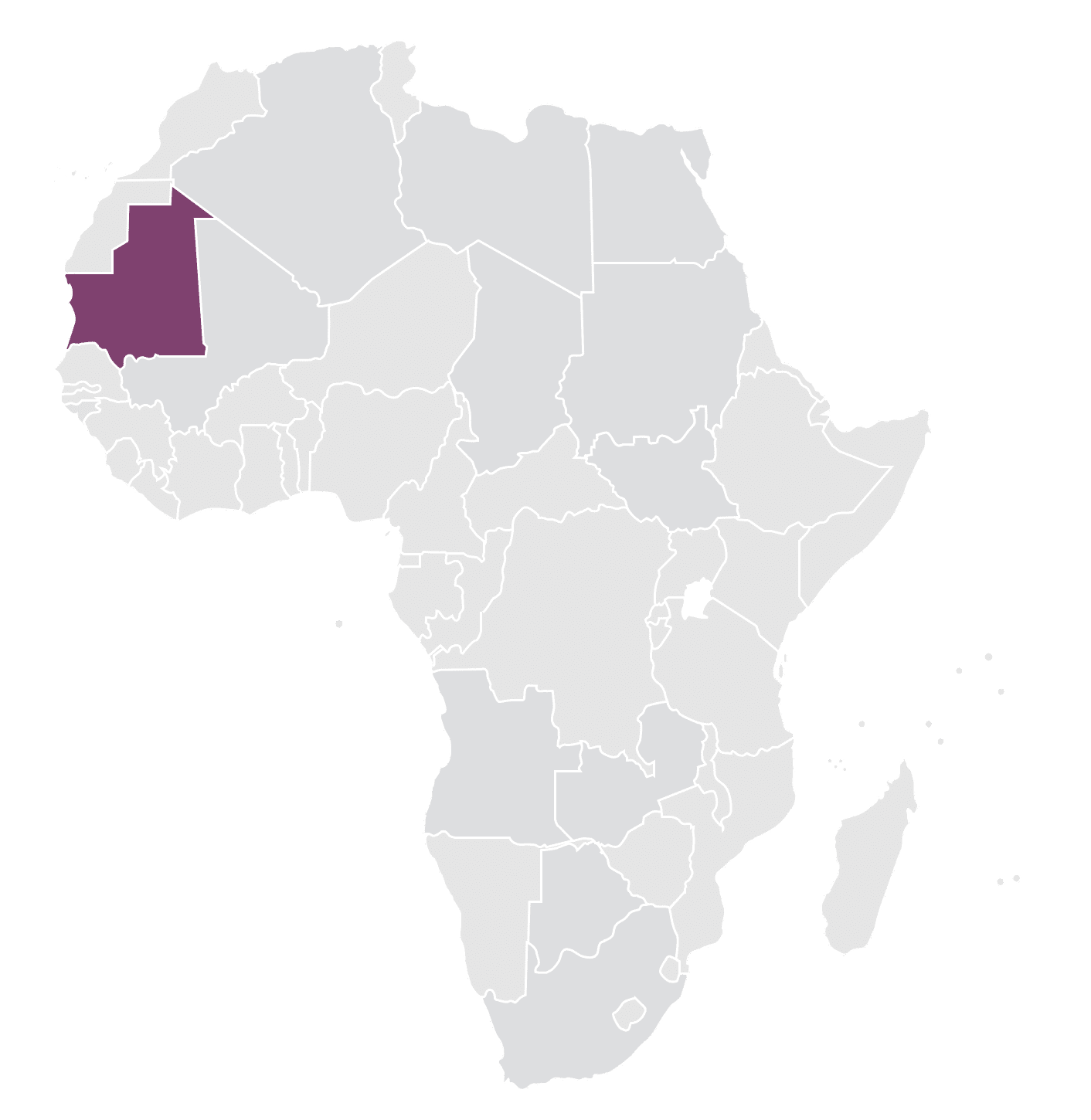

I don’t know if it’s the Sahara’s harshness that has made people accustomed to this. But I do know that one in five Mauritanians is still a slave. Officially abolished in 1981, slavery still runs through the veins of this nation like a poison. This is unmatched by any other country. It wasn’t until 2007 that the Mauritanian government legally recognized slavery as a crime, but this has merely been a token gesture. It’s met with a dismissive smile, akin to an imaginary law against riding a donkey without a seatbelt.

Slavery in Mauritania is inherited, and there’s still a belief that being owned by someone else paves the way to heaven. This doesn’t make much sense in the harsh Sahara, because slavery simply doesn’t make sense at all.

Slavery is like the Sahara itself. It dictates when and where you have to go. In August, Mauritania’s soil burns red-hot, not allowing people to live where they want. They have to find a place and a job that lets them survive, even if it means just one meal a day. We can’t change their need to move any more than we can repeal the Sahara’s harshness with a bill.

What if we followed these people? Followed them wherever they must go. We could feed them, support, and help not in one place, but on their journey, and we could firmly believe that someday they will find their own path to freedom.