Today, we want to dispel the myth of a man fleeing his homeland, who instead of fighting for its freedom, gets on a dinghy and takes flight. He sets off with his mobile phone in his hand, and from the moment he sets foot on European soil, he is no longer a coward, but a fearsome stranger who crosses not only the border lines, but also the boundaries of our sense of security.

They deserve a few words, because although the women and children in the camp suffered the same fate as the men, the latter are the least sympathised with. Stereotypical thinking hurts them greatly. Of course, there are people among them who would prefer to take shortcuts, but if there were 4 000 of our fellow countrymen gathered in one place, would there not be among them those who would rather steal than work?

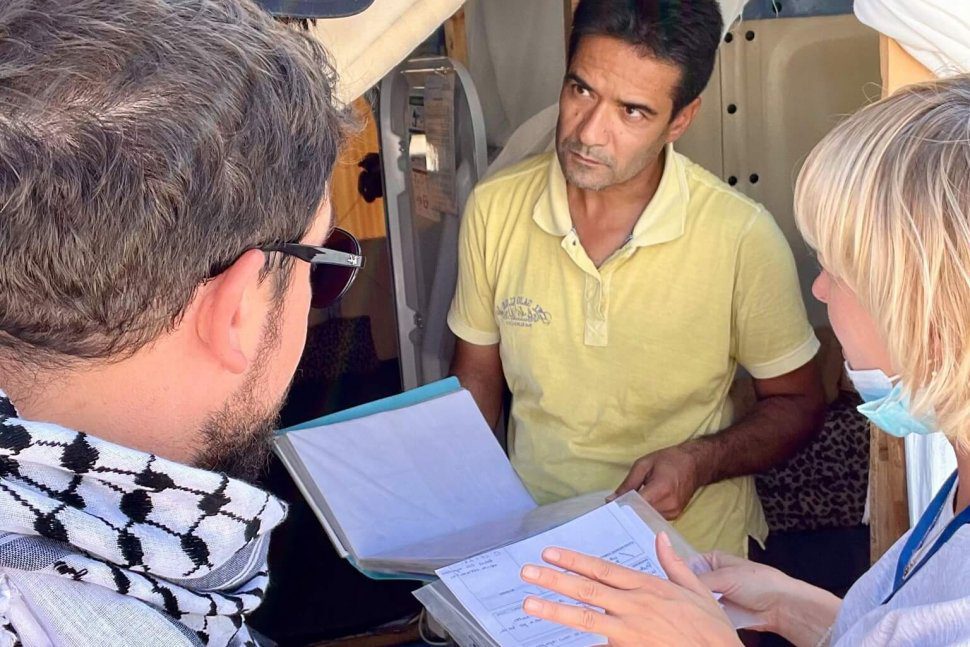

Every day we spend a few hours in the camp. We visit the families, we spend time with them, drink tea together and talk about our problems and sorrows. We do our best not to be remembered as a pat on the shoulder, but as friends who are helping as much as they can. The more time we spend with these people, the more respect we have for fathers and single men who, when asked to help, never say no.

Every day we thank the interpreter for the time he spends with us. He is a 14-year-old Afghan boy who visits the families with us. “It is I who thank you for giving us your time, the people living in this terrible place,” answers Mohamed, hoping that tomorrow he will be able to help us once again.

The vast majority of men in the camp are fathers. During the day, they are the ones who take care of the children, allowing the women during this time to prepare a meal, go to the doctor, do the laundry or comfort the neighbour from the adjacent tent who can no longer stand life in captivity and is no longer coping. They are the ones who build swings for their children out of vegetable crates and pallets. They teach the children how to ride a bicycle and make sure no harm comes to them in an area full of dangerous obstacles.

The section for single men only appears to be a dark corner of the camp, where it is best not to venture. During the last stay it was there that we visited on the first day. All it takes is a smile, a moment of sincere conversation. When noticed, everyone willingly invites you in and is keen to talk about themselves. About how hard it is for them, how unwanted they feel. There are teachers and engineers among them, whose will to survive and common sense made them leave their life’s achievements, lucrative jobs and become unwanted intruders.

It is the residents of the single men’s section who help us to distribute the meals to the sick and to pregnant women every day, showing up punctually at 14:15 at the meeting point. Everyone knows what to do, taking a map in one hand and a bag full of meals in the other. They never complain. They work efficiently, because they know that the meals must reach the families while they are still warm.

Nikos is well aware that the guys in the single men’s section are shunned by most organisations. When he gets a call that a trader or restaurateur on the island has a pallet of juice, fruit or sweets to give away, he often takes them to the boys. The first time that he arrived in a minibus loaded to the brim and set it down in front of the tents in that section, the men rushed over to offer help and asked who they should deliver the parcels to. When it turned out that it was for them, they started dancing with joy that finally someone had thought of them.

You only have to spend a few days here and talk to these men to realise that someone intended to make us feel threatened, creating stereotypes which, here in Europe’s largest refugee camp, have nothing to do with reality. They are mostly excellent fathers, husbands and bachelors. People who dream of freedom and safety for themselves and their families, fleeing persecution with the same fear and helplessness as the women and children.